Amy Ingram and Matthew Cresswell interview Glenn Moss for the

WITS 100 tributes, and the

Fak'ugezi African Digital Innovation Festival

September 2022

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IzAvPZczfwQ&ab_channel=MatthewCresswell

George Bizos

1928-2020

Remembering George Bizos

George Bizos was as much a master tactician as he was a highly skilled defence lawyer.

His mission was to protect clients charged with political offences as far as possible, but always advising them not to compromise their beliefs, organisations and principles in an effort to limit the likely jail sentences.

As a principled and ethical advocate, he would not collaborate in fabrication. I remember him pointing out to me that if those with morals facilitated lies, what chance could there ever be for a more ethical legal system in the fullness of time.

George always reminded clients that, if found guilty and sent to prison, they would be serving their sentences with the highest levels of political leadership. Opportunistic compromising of beliefs and principles, or lying about core values and actions in an effort to lessen jail time, might render relations with other political prisoners very difficult.

That was the tactical balance George helped his clients negotiate. Weaken the prosecution’s case where possible. Limit the damage to the accused without unnecessary compromise. In those rare cases where acquittal might be possible, pursue that with energy and rigour.

And in the many inquests into deaths of political detainees, George always knew that the chances of a finding that torture was a common part of security police interrogation techniques were limited, partly because of the type of magistrates who routinely heard inquests into political deaths. But George was a masterful tactician in extracting the maximum damage that could be inflicted on security police and those who collaborated in the system of long-term interrogative detention without trial.

This he would do by persistent, dogged and sometimes brutal cross-examination of police and other state witnesses. It is, indeed, his ferocious cross-examination skills for which George will be particularly well remembered.

During the year-long Nusas trial of 1976, where I was privileged to be represented by a legal team which included George, Dennis Kuny, Raymond Tucker and Geoff Budlender, and led by Arthur Chaskalson, I was often witness to George’s fine combination of integrity and tactical skill.

As described in my book The New Radicals, George had travelled to Robben Island to consult with Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Govan Mbeki on some issues of ANC history and tactics which had arisen in the Nusas trial. Although not central to the trial, this did provide George with an opportunity to visit three of his Rivonia trial clients. As George describes in his autobiography, Odyssey to Freedom, ‘The three were willing to be called as witnesses for the defence and greatly admired the dedication of the young people on trial. I was to thank them for risking their freedom to call for the release of political prisoners’.

Mandela explained to George that a number of Robben Island prisoners were suffering from low morale. Many had been in jail for ten years and they feared they were being forgotten. Suddenly, a group of young white students were running a national campaign calling for their release and integration into a political process. This provided an important boost to flagging spirits.

A fierce debate ensued amongst the defence team and the accused about whether to accept Mandela’s offer to testify. The defence lawyers properly advised us that bringing Mandela to court in Johannesburg might prejudice our chances of acquittal, or even provoke stiffer sentences in the event of being found guilty. The whole defence team, including George, was at pains to point out that calling Mandela as a witness might prejudice us, but that it was our tactical decision, not a legal determination. And George, ever the strategist, reminded us that we would be subjecting Mandela to cross-examination by the state, which could be problematic for both him and the ANC.

It fell to George to prepare me to give evidence in my defence. Over a period of six weeks, we met over many nights at his home, often after long and tedious days in court. I do not think I was an easy client, tending to default into debates over political theory and strategy, rather than preparing the evidence I would deliver. On one occasion, we differed strongly about whether I would describe myself as a democratic socialist or a social democrat – or even a radical liberal. George advised that it might be a bridge too far for the presiding officer to accept the careful distinctions I wanted to draw between communism, socialism, democratic socialism, social democracy and liberal radicalism, but left the choice to me. In the event, I do not think the prosecution asked me that question, to everyone’s relief.

Twenty years after our acquittal in the Nusas trial, George reminded the Nusas 5 that Mandela – now president of South Africa – had often reiterated how important the Nusas campaign to release all political prisoners had been, and that one day he wanted to thank the leaders of it. And so it came to be that, one hot December day in 1996, Mandela was guest of honour at a lunch at my home, together with others who had been imprisoned at the time, or whose close family members had been jailed.

It was George who secured Mandela’s presence at this gathering. He did not easily forget his clients or his friends - just as we will always remember him.

Glenn Moss

10 September 2020

This article appeared in slightly different form in the Daily Maverick of 10 September:

www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-09-10-george-bizos-was-as-much-a-master-tactician-as-he-was-a-highly-skilled-defence-lawyer/

George Bizos was as much a master tactician as he was a highly skilled defence lawyer.

His mission was to protect clients charged with political offences as far as possible, but always advising them not to compromise their beliefs, organisations and principles in an effort to limit the likely jail sentences.

As a principled and ethical advocate, he would not collaborate in fabrication. I remember him pointing out to me that if those with morals facilitated lies, what chance could there ever be for a more ethical legal system in the fullness of time.

George always reminded clients that, if found guilty and sent to prison, they would be serving their sentences with the highest levels of political leadership. Opportunistic compromising of beliefs and principles, or lying about core values and actions in an effort to lessen jail time, might render relations with other political prisoners very difficult.

That was the tactical balance George helped his clients negotiate. Weaken the prosecution’s case where possible. Limit the damage to the accused without unnecessary compromise. In those rare cases where acquittal might be possible, pursue that with energy and rigour.

And in the many inquests into deaths of political detainees, George always knew that the chances of a finding that torture was a common part of security police interrogation techniques were limited, partly because of the type of magistrates who routinely heard inquests into political deaths. But George was a masterful tactician in extracting the maximum damage that could be inflicted on security police and those who collaborated in the system of long-term interrogative detention without trial.

This he would do by persistent, dogged and sometimes brutal cross-examination of police and other state witnesses. It is, indeed, his ferocious cross-examination skills for which George will be particularly well remembered.

During the year-long Nusas trial of 1976, where I was privileged to be represented by a legal team which included George, Dennis Kuny, Raymond Tucker and Geoff Budlender, and led by Arthur Chaskalson, I was often witness to George’s fine combination of integrity and tactical skill.

As described in my book The New Radicals, George had travelled to Robben Island to consult with Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Govan Mbeki on some issues of ANC history and tactics which had arisen in the Nusas trial. Although not central to the trial, this did provide George with an opportunity to visit three of his Rivonia trial clients. As George describes in his autobiography, Odyssey to Freedom, ‘The three were willing to be called as witnesses for the defence and greatly admired the dedication of the young people on trial. I was to thank them for risking their freedom to call for the release of political prisoners’.

Mandela explained to George that a number of Robben Island prisoners were suffering from low morale. Many had been in jail for ten years and they feared they were being forgotten. Suddenly, a group of young white students were running a national campaign calling for their release and integration into a political process. This provided an important boost to flagging spirits.

A fierce debate ensued amongst the defence team and the accused about whether to accept Mandela’s offer to testify. The defence lawyers properly advised us that bringing Mandela to court in Johannesburg might prejudice our chances of acquittal, or even provoke stiffer sentences in the event of being found guilty. The whole defence team, including George, was at pains to point out that calling Mandela as a witness might prejudice us, but that it was our tactical decision, not a legal determination. And George, ever the strategist, reminded us that we would be subjecting Mandela to cross-examination by the state, which could be problematic for both him and the ANC.

It fell to George to prepare me to give evidence in my defence. Over a period of six weeks, we met over many nights at his home, often after long and tedious days in court. I do not think I was an easy client, tending to default into debates over political theory and strategy, rather than preparing the evidence I would deliver. On one occasion, we differed strongly about whether I would describe myself as a democratic socialist or a social democrat – or even a radical liberal. George advised that it might be a bridge too far for the presiding officer to accept the careful distinctions I wanted to draw between communism, socialism, democratic socialism, social democracy and liberal radicalism, but left the choice to me. In the event, I do not think the prosecution asked me that question, to everyone’s relief.

Twenty years after our acquittal in the Nusas trial, George reminded the Nusas 5 that Mandela – now president of South Africa – had often reiterated how important the Nusas campaign to release all political prisoners had been, and that one day he wanted to thank the leaders of it. And so it came to be that, one hot December day in 1996, Mandela was guest of honour at a lunch at my home, together with others who had been imprisoned at the time, or whose close family members had been jailed.

It was George who secured Mandela’s presence at this gathering. He did not easily forget his clients or his friends - just as we will always remember him.

Glenn Moss

10 September 2020

This article appeared in slightly different form in the Daily Maverick of 10 September:

www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-09-10-george-bizos-was-as-much-a-master-tactician-as-he-was-a-highly-skilled-defence-lawyer/

Glenn Moss remembers George Bizos (video)

Memorial service, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

11 November 2020

In memory of Phil Bonner

1945 - 2017

Reviews and interviews

The age of activism: the Franschhoek Literary Festival discussion with Glenn Moss (author of The New Radicals) and Malaika Wa Azania (author of Memoirs of a Born Free). Audio recording. Moderated by Professor Jonathan Jansen.

'Feats of an innovative generation'. Gavin Evans reviews The New Radicals for the Mail & Guardian

After reading The New Radicals, long serving public intellectual and US activist Harry Boyte opens a discussion on parallels and differences between 1970s youth activism in South Africa and the United States

Ben Fogel reviews The New Radicals for the

Journal of African and Asian Studies

This is WITS! Interviews with Wits alumni, including Glenn Moss, author of The New Radicals

Anthony Egan reviews The New Radicals for theJournal of the Helen Suzman Foundation

The London launch at Housmans

'Spotlighting the new radicals' role'. Nalini Naidoo reviews The New Radicals for the Witness

The Africa Report: a review of The New Radicals

Michele Magwood interviews Glenn Moss for the TM LIVE Book Show

The London launch: a profile in The South African.com. News for Global South Africans

The Kalk Bay Books launch: photographs

Ndifuna Ukwazi seminar video

Review by Martin Plaut

Peter Vale's review in the Mail & Guardian

Shannon de Ryhove interviews the author for Polity

The author

Glenn Moss was a student leader at Wits University in the 1970s. Detained and charged under security legislation in the mid-1970s, he was acquitted after a year-long trial. He went on to edit Work In Progress and the South African Review, head Ravan Press, and then work as a consultant to South Africa’s first post-apartheid government. For more details, go to

www.thenewradicals.com/the-author.html

Glenn Moss was a student leader at Wits University in the 1970s. Detained and charged under security legislation in the mid-1970s, he was acquitted after a year-long trial. He went on to edit Work In Progress and the South African Review, head Ravan Press, and then work as a consultant to South Africa’s first post-apartheid government. For more details, go to

www.thenewradicals.com/the-author.html

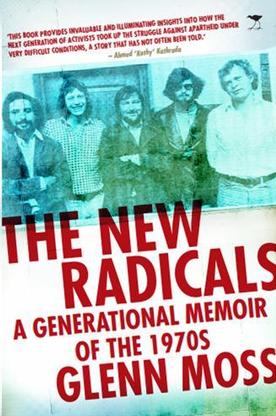

The book

By the end of the 1960s, opposition to apartheid was in disarray. Yet in the space of a few short years, major and radical challenges developed that would set the country on a new path.

This lively and original book tells the story of a generation of activists who embraced new forms of opposition politics that would have profound consequences. In the process it rescues the early 1970s from previous neglect and shows just how crucial these years were in the struggle to transform society.

It explores the influence of Black Consciousness, the new trade unionism, radicalisation of students on both black and white campuses, the Durban strikes, and Soweto 1976, and concludes that these developments were largely the result of home-grown initiatives, with little influence exercised by the banned and exiled movements for national liberation.

‘A much-needed and engrossing personal account of the embryonic student and black trade union movements of the early seventies, and how this younger generation of activists, both black and white, battled to wage struggle at a time when apartheid was at its height, and the liberation movements at their weakest. Through their actions, the radicalism of this generation defined a new politics of opposition.’

Barbara Hogan, former Minister of Health and of Public Enterprises and political prisoner

By the end of the 1960s, opposition to apartheid was in disarray. Yet in the space of a few short years, major and radical challenges developed that would set the country on a new path.

This lively and original book tells the story of a generation of activists who embraced new forms of opposition politics that would have profound consequences. In the process it rescues the early 1970s from previous neglect and shows just how crucial these years were in the struggle to transform society.

It explores the influence of Black Consciousness, the new trade unionism, radicalisation of students on both black and white campuses, the Durban strikes, and Soweto 1976, and concludes that these developments were largely the result of home-grown initiatives, with little influence exercised by the banned and exiled movements for national liberation.

‘A much-needed and engrossing personal account of the embryonic student and black trade union movements of the early seventies, and how this younger generation of activists, both black and white, battled to wage struggle at a time when apartheid was at its height, and the liberation movements at their weakest. Through their actions, the radicalism of this generation defined a new politics of opposition.’

Barbara Hogan, former Minister of Health and of Public Enterprises and political prisoner

‘In the dark days of the early seventies, when the news filtered through to Robben Island of a campaign to release political prisoners, waged by a small group of left-leaning, white students, it buoyed our spirits immensely. This book provides invaluable and illuminating insights into how the next generation of activists took up the struggle against apartheid under very difficult conditions, a story that has not often been told.’

Ahmed ‘Kathy’ Kathrada, Rivonia trialist and Robben Island prisoner

Ahmed ‘Kathy’ Kathrada, Rivonia trialist and Robben Island prisoner

‘Fascinating and important insight into the emergence of a brave young radicalism of the early 1970s embracing

white campuses, black consciousness and trade unionism, which raised questions and challenges not only for the

apartheid-capitalist nexus but also for the mainstream liberation movement.

‘Those in exile and in prison strove then to discern what was new and possible. Whilst hope for change was

reinforced by these developments, there was also a degree of concern and prejudice. This was compounded by

lack of clarity from afar, as to whether such emergent forces would be loyal to the ANC-SACP alliance and how

to provide leadership to them.

‘Looking back, there is much need for honest reflection and the author does us a service with his well-worked

research and writing. It leaves one with tantalising thoughts as to whether the incipient democratic left challenges from civil society and trade union circles in South Africa today might fundamentally change our political

landscape.’

Ronnie Kasrils, chief of intelligence for Umkhonto we Sizwe and government minister from 1994 to 2008

white campuses, black consciousness and trade unionism, which raised questions and challenges not only for the

apartheid-capitalist nexus but also for the mainstream liberation movement.

‘Those in exile and in prison strove then to discern what was new and possible. Whilst hope for change was

reinforced by these developments, there was also a degree of concern and prejudice. This was compounded by

lack of clarity from afar, as to whether such emergent forces would be loyal to the ANC-SACP alliance and how

to provide leadership to them.

‘Looking back, there is much need for honest reflection and the author does us a service with his well-worked

research and writing. It leaves one with tantalising thoughts as to whether the incipient democratic left challenges from civil society and trade union circles in South Africa today might fundamentally change our political

landscape.’

Ronnie Kasrils, chief of intelligence for Umkhonto we Sizwe and government minister from 1994 to 2008